Usually cursing doesn’t bother me, but the man seated next to me, having erupted in a fit of teeth-baring aggression, looks almost exactly like my grandfather. I glance sideways at him after he spit three ugly words down at his tray table. He has papery white skin with red blotches that match the color of the Canadian passport he is clutching and show through his beard like dry patches of earth in withering grass. The thin white hairs are strong at his chin but fewer and far between as they struggle to reach his ears. Although his words did not match my conceptions of Canadian politeness, his accent was similar to the country Midwestern one my grandfather affects to match the people of the Wisconsin town where he used to spend his summers. The stewardess had just confirmed what the co-pilot had broadcast to his cabin: we would not be landing in Amsterdam on time and my neighbor had missed his connecting flight to Vancouver. I already knew I had missed mine to Boston.

I had spent the past week in Berlin, visiting my girlfriend after time apart, and I had never travelled alone before. Now I am circling through Amsterdam’s air space, and smiling at the baby across the aisle from me. I make eye contact and engage my entire face in a wide smile. The wriggling baby looks back from its mother’s shoulder and seems to cease its nervous fidgeting and calm down some. I had heard that a baby’s favorite sound to make was “pa!” because the sound of the consonant p exploded from pursed lips and out into the world unlike any other, allowing the baby to revel in its own power and ability to disturb and shape its environment. That is why I always smile at babies whenever I could catch their eyes, to show him or her that they had an effect on me, as I was smiling for the baby and the baby alone. The baby instinctively knows this, of course, and is reaffirmed as being at the center of the universe. It calms down, and sometimes he or she even smiles back.

As the stewardess readies the cabin for landing, I finish a magazine article I had been reading. It was about how the author’s brother had essentially disappeared, to the horror of their family, who later learned that he had been arrested for failing to pay child support. The author explains that the prisoner’s right to a single phone call is a myth, and says her mother only received calls from a machine. An automated computer voice from the correctional center, asking for money to be placed in a prepaid account to contact the son. She thought it was a scam, a deception, and never paid, never called back, just let the monotone messages fill her voicemail. The author reflects that her brother was made missing, yet that those like him had always been missing, inexplicably ignored, irretrievably lost. I place the magazine in my bag, and the plane descends.

We finally land after circling the Amsterdam airport to avoid “inclement weather,” and my neighbor quickly stands up and pushes his way toward the front of the line. I calmly join the line of passengers, gathering their things from overhead and slowly filing out of the plane. The flight attendant had reassured us that we could board the next flight to our destination and it would be free of charge. As we spill out into the airport, I seem to be the only one alone. Families, couples, groups of friends grumble about how their flights had been missed, and some rush off to their next gate. I stand watching them, and anxiously come to the realization that I did not know what to do next. As people depart I notice that the airport is named Schiphol and that it is unremarkable. It’s cavernous, sleek, and modern, full of signs and symbols pointing crowds where to go. People throng ahead, but just outside the arrival gate the area is calm, empty. I look for some one to ask about how I could get a ticket for the next plane to Boston as the flight crew enters the airport. A stewardess anticipates my question and directs me to a kiosk of computer screens, telling me it would be easier to type my problem into the machine instead of talking to some one at an information desk. I doubt this, but line up for the kiosk. Once the other exasperated passengers had gotten a new ticket, I type in my name and destination. The screen tells me the next flight isn’t until tomorrow morning at 9 and that now it is only 2 in the afternoon. I have no choice. The computer prints me a boarding pass and then asks me if I would like to stay at a nearby hotel for a night, or if I would like 40 euros instead. I imagine spending all night sleeping in a hard metal chair in a corner of the airport, or stumbling through the streets of Amsterdam, begging locals who only spoke Dutch to point me in the direction of a cheap inn. I pick the free hotel stay. The machine dispenses three flimsy pieces of paper: one for a bus ride, one for a free meal, and one for a one-night stay at the Hotel Van der Valk A4 Schiphol.

I never knew or even thought to research what “Schiphol” meant, if it was the name of a Dutch region or a famous Dutch person, or if it was a focus-grouped series of sounds meant to subconsciously implant ideas of comfortable and easy air travel into the minds of European tourists. Van der Valk A4 meant even less. I walk through the airport, past gates, vending machines, and cafes, looking for the first exit that might lead to a bus to the hotel. I briefly consider going into Amsterdam, and seeing the sights, visiting the van Gogh museum. If I were to do so, I would have had no idea how to get back to my hotel. Was there a subway or a bus or a cab that could take me from the center of Amsterdam to the Van der Valk A4 Schiphol? I don’t think so. I imagine the hotel as an isolated colony of the airport itself, that can only be reached by the bus that the lifeless computer kiosk just determined I must ride, and it seemed, also prohibited me from deviating from that instruction.

I walk under signs buzzing and flashing out arrivals and departures, times and destinations, finally reaching a door, and leaving the airport. I join a massive crowd of people, all arrayed into several lines, filling in and spilling around the glass shelter of a bus stop. Europe is in the midst of an early summer heat wave and the sun beats down hard on the group, who like me, were the sorry result of missed connections and unpredicted weather patterns. Each line of irritable, sweating people is bound for a specific bus that would take them to a specific hotel in the surrounding area. I found a schedule on the glass shell that provided no shade and no respite from the heat, and discover the bus leaving for the Van der Valk A4 was leaving in 5 minutes. I wait among the others, listening to them gripe, call into their bosses, and comfort each other by some saying hey at least the hotel is free! Eventually, a bus pulls up to the airport, and its side is emblazoned with the garish logo image of a black toucan, its beak rigid, bulbous, and sickly yellow beneath a single beady red dot for an eye. A mass of people exit the bus, and one by one people in my line start to recognize that we might not all fit, and begin jockeying for position. I push up with the rest, moved by the flow and singular mentality of the crowd: this trip is the one that we will not miss. An older woman graciously allows me to step in front of her and board the bus. I move silently to the back, making myself as small possible, not taking a seat, but standing still and leaning forward against a luggage rack.

Bodies fill the bus, window to window, and I peer over black suitcases and watch as the landscape unfolds and then rushes past me. The land is unbelievably flat, a green lawn baked in the sun and nothing else. My sight is forced straight to the horizon with no discernible objects or landmarks in the way. The rigid blades of grass made an ocean without waves or shore. The cloudless blue sky was as oppressively blank as the land, the two meeting at a firm crease. The land was so low, vast, and empty as to seem infinite, and the line to the horizon so sharp that the landscape appeared like an unfinished painting that my eyes and brain strained to fully bring into comprehension. As my body began to reject these surroundings and the bus’s rapid movement through it, I turned my head from the bright, near-terrifying expanse.

Looking around me, people from all over filled the bus. An Asian woman and a man wearing an baseball hat entertain their child with French songs, rocking her stroller ever so slightly so as not to disturb those sitting next to the aisle. A wiry man next to me talks in English to an old woman wearing a tie-dye dress of soft pastel rainbow colors stained into thin white fabric. He tells her that he was travelling through Europe alone and was heading back to his home in Georgia before their stranding. When the woman in the rainbow dress tells him that she is a missionary, I notice the large wooden crucifix hanging from her neck. She speaks in an English accent, and tells him softly about how she had travelled to the continent to help support a congregation at a brand new Church in Germany. The soft but strained quality of her voice lets on that she is quite old, and as I stare out the window, I no longer listen to their conversation and only hear its noise, American, English, masculine, feminine, firm, soft. I remember my last bus ride from days before, during a day trip from Berlin to Prague. On our way back, the bus had driven right through Dresden at night, and for the first time I found myself in a city that my country had completely destroyed. I saw the large domed Cathedral as we passed a line of buildings, the architecture following the dark curve of the river. I had tried to imagine Dresden as others had: jewel box, fire storm, lunar surface.

A child somewhere in the thicket of people by the driver shouts and I remember where I am. The bus pulls up in front of a hotel made of white painted concrete, and a bright blue facade hung over the patio has the words “Van der Valk A4 Schiphol” printed across it. We all step out, and I see another bus schedule, emblazoned with the garish, staring toucan, on the side of the building. I have to take the 6 AM bus the next morning if I was going to make it to the airport on time. I notice a bench and another glass shell for a bus station, and again consider going into Amsterdam, but I realize it could take hours to get there and I wouldn’t know which bus to take there and back. Taking a bus and leaving this hotel seems to me like leaving an island for a journey across the ocean in a life raft. The crowd of people again push itself into the hotel, and swarm the lobby. The lobby is painted green with a low ceiling, floral patterned upholstered chairs are arranged in one corner, and a dim brass chandelier hangs from the center of the ceiling. A frustrated couple speaks Chinese angrily to a man at the front desk, who does not understand them, but gives them a room key and a voucher for a free dinner at the hotel’s restaurant. Families of various size and origin complain in Spanish, German, tongues I couldn’t place. What seems like an entire Sikh wedding had evidently had their travel disrupted, and families of turbaned men argue loudly with women wearing massive earrings that shudder as they speak.

Approaching the desk, I feel like I had been shipped there by some unknown entity, like I was a parcel arriving in the mail. My journey tracked, disrupted, and rerouted all through conversation and information transfers that I was for some reason, not privy to. I realize I had no clear idea of why I am here, in this particular lobby, or how exactly I had gotten there. The workers at the desk tell me I am staying in room number 1207, and they also give me a voucher for a free dinner. I am in the Van der Valk Schiphol A4, and there is nowhere else I need to go, and nowhere else I could go, as the hotel is nowhere, a building off of the highway coming from nowhere and leading nowhere, cutting through nothingness. The entire hotel should not have existed, and in a better world it did not. It was the product of clerical error, unforeseen mistakes in weather predictions, poor airport design, faulty aviation engineering, flawed logistics, and miscommunication. The architecture and bureaucracy of the place was accident, spreadsheet typos, and irreversible entropy as much as it was concrete, carpet, and room check-ins. Not a single person there chose or wanted to be at the hotel. Yesterday, none of the hotel clientele planned or could have predicted that they would be there the following day. Like jail guards, the hotel workers, hidden behind doors and watching behind desks, simply served and surveilled a rotation of the accidentally marooned. We could never truly know each other.

Since neither I nor any one else at the hotel could experience the Netherlands, only its very edge, the hotel was decorated with things that confirm a tourist’s kitschiest visions of the country. By the entrance to an indoor swimming pool, a map of the low countries demarcated with childish drawings of windmills, tulips, and landmarks, instead of legends or roads, hangs on a wall. By the elevator to my room the entire wall is plastered with an enlarged reproduction of Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, except the militiaman in red and the girl to his left wear electronic headphones. I could not conceive what music they were listening to and if it fortified them on their watch. Another massive wall-sticker of The Anatomy Lesson featured one of Rembrandt’s students jotting notes on a laptop computer, and another taking a picture of the corpse’s flayed arm with a mobile phone. The corridor leading to my floor was decorated with repeating blue and white designs featuring floral lace and country towns, tulips, windmills, and children kissing and ice skating. I had been shrunk and placed in a porcelain jar from Delft, trapped inside so I could never appreciate its beauty or value. I am being digested by a clumsily-edited Frankenstein of the Dutch Golden Age. In my room, I see a van Gogh self-portrait, and a Heineken bottle cap on the lobe of his still-attached ear winks at me.

In room 1207, complete with white carpeting, orange furniture, and an en suite bathroom, I go to the doors at the end, open them, and step onto the balcony. I look out and see the rest of the hotel rooms, with their small unimpressive balconies, curving around an empty concrete parking lot. I suppose it was an area where trucks delivering food or linen to the hotel could park. I go back into the room, and let light come in from the coffin-shaped balcony and lie on the bed in silence. I begin to drift towards sleep, and the Chicago of one winter, years ago, fills my mind. My parents and I had visited my grandfather family there, but our flight back to the east coast had been cancelled due to extreme weather conditions. A blizzard had consumed city and temperatures had dropped to an astounding negative 45 degrees, all flights were grounded for days. My parents and I stayed at a hotel, its restaurant and bar were not properly heated and the extreme cold seemed to flow into the space through its large glass windows. The second day we walked outside to a nearby mall to stave off maddening boredom, and any piece of skin that was left exposed immediately felt like it was burning when it touched the air. A homeless person held a sign in front of the mall, and was so wrapped in coats and scarves I could not see their face. When I passed the person again, I realized I never saw them move and questioned whether they were alive, or if they were just petrified and frozen on the spot. As we waited to fly out, we were outside of time. The present and future, and their steady progress and the events they held, had become a foreign land.

When the cold subsided enough for planes to leave, my family took a cab to the airport. An older Greek man drove us slowly, but the car still fish-tailed on the frozen road. Feeling nauseous as the car whipped my body, I looked out at the city skyline and the tall buildings seemed like shard of ice, sticking up from the ground and thrown out toward the white windswept lake, frozen smooth as a polished dinner plate.

Waking fully, I think of the hotel’s pool that I had passed earlier, and decide that although I could not go to Amsterdam, I might as well do something at the hotel. Quickly, the desire to swim, to submerge myself in water and no longer feel the weight of my body, commands me. I have no bathing suit, but maybe they sell them at the front desk or at some small shop in the hotel. I take the elevator down, and see next to it a sign displaying a blueprint for an expansion of the hotel coming in the following year, as if the error and relocation is expected to increase exponentially. The garish toucan looks out over the digital rendering of the building with an intricate gridded floor plan, additional stories, and a new bar lounge. Seeing this blueprint, and the floorplan with its gridded, empty cells representing the bird’s eye view of rooms and tables, I am reminded of Berlin’s abandoned airport. My girlfriend, her roommate, and I strolled through an abandoned airport that the city had not torn down, but allowed its runways to be turned into a public park for walking, bike riding, and concerts. As the sun set, we walked under the crumbling, but still imposing, air traffic control center that stood above the ground like a grand decrepit dome. The terminal building below arched around the pavements, reflecting the sun off its numerous small rusted windows. We soon approached a large fence, and when I looked through its holes, I saw it contained a large area filled with hundreds of little one-room buildings, like bright white office cubicles, that abutted the abandoned airport. Behind the fence, a group of children chased each other, running and riding bikes around a block of the white squares, laughing and screaming. They were not Germans. I was told this stretch of runway had been transformed into a refugee housing center. I saw a sign, and noticed the words Unterkünfte in bold. I asked what that meant, and why the refugees were all fenced off from the park. My companions didn’t know, and they said the fence was for privacy. As I walked away, I saw an older man perched at the edge of one of the identical white boxes as if enthroned, holding a gleaming, golden hookah pipe. He watched the children, his eyes commanding the airstrip, as the children ran, encircling him again and again.

On the other side of that fence, in the jolting cab in Chicago, in this hotel, anxiety writhed in my mind and wormed through my body. My stomach is hollow, the back of my neck itches and aches. Looking away from the blueprint, I imagine that when I open the door to the indoor pool, I will find myself in the room, sitting by the water. He, my exact double, will walk up to me and demand I tell him what I was doing there, yell that I was never supposed to be here, and violently insist I leave to where I had come from. I walk towards that door, but by the entrance I find, as if in a miracle or a mirage, a vending machine full of small plastic bundles, zipped up to hold bathing suits inside. I followed the machine’s instructions and press the buttons on its screen. I buy a pair of trunks in my size, and the machine violently clangs and then gently whirred. Behind glass its coiled wire slowly, gradually, spins and retracts until my one black bundle drops down with a painful grace I can barely endure.

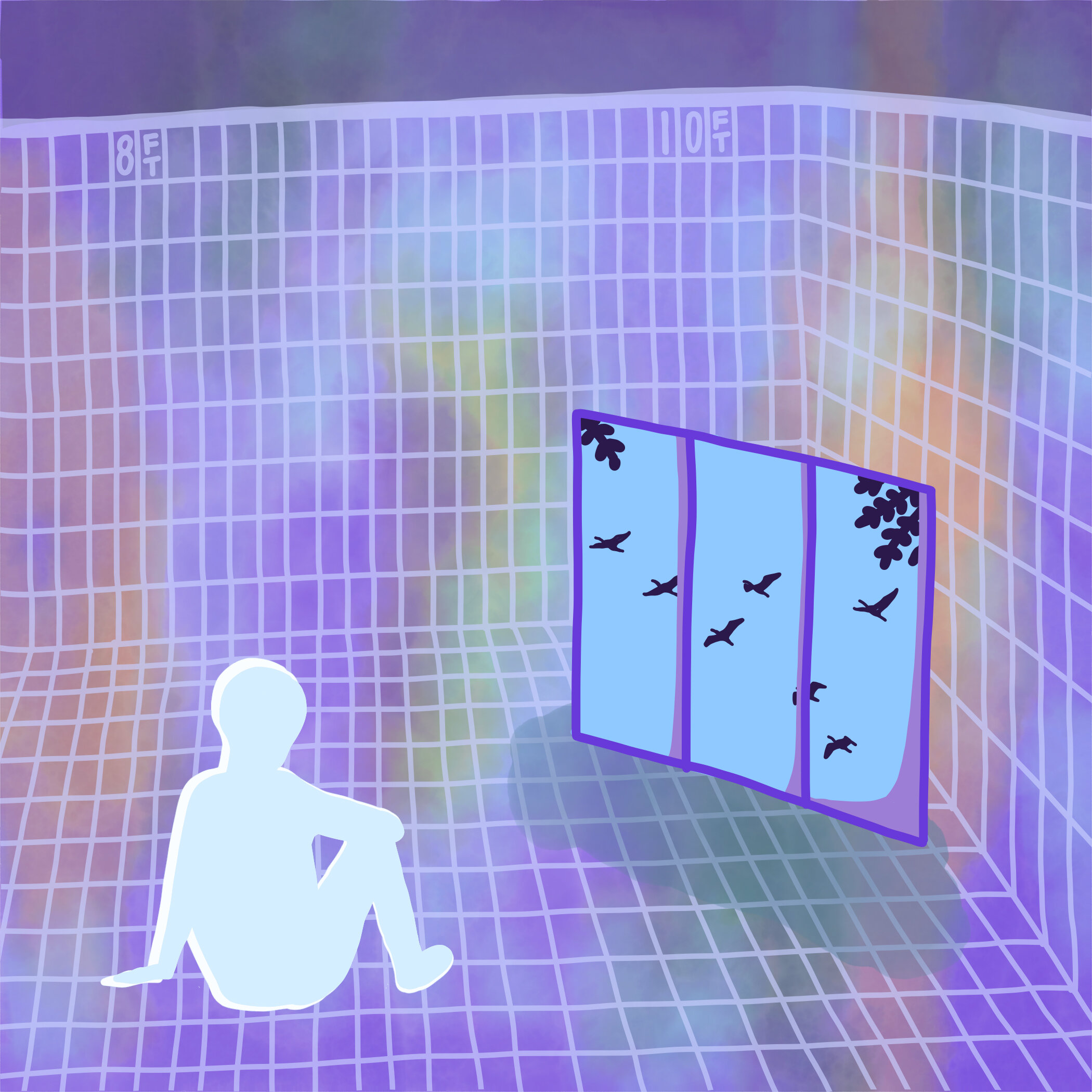

Holding this precious bundle, I search for a place to change and open a door to a locker room. Instead I enter the waiting-room of a sauna and see a woman in a white two-piece bathing suit, reclining on a chair under a tanning light. She makes no movement at all, her eyes stare blankly up and no gesture or intake of breath show that she is aware of my presence. The light above her buzzes and bathes her body in a sickly hot orange light. Finding a bathroom, I clothe myself in the fruit of that whirring metal tree’s corkscrew branches. The bathing suit was shorter than any trunks I had worn before, I felt nauseous seeing my pale thighs. Exiting the bathroom, I finally open the door to the pool. The rectangle full of water is in a space dominated by glass. The wall behind me is the concrete of the hotel, and the other three walls of the space and the ceiling are panes of glass erected in a grid, so the swimmers could look up at the blank sky or out at the infinite grass fields past the highway. Two British men mutter to each other at one side of the pool. I stand across from them and watch the water lap at the edge of the pool’s blue tiles by my feet. With a step, I let myself fall in, a lifeless plunge.

As I crash through the water, I close my eyes and slide under, determined to stay there as long as I can. As I linger beneath the surface, I let my body go limp, the rippling of the water and the voices of the men fade away. The water is cool until my body can sense it no more. The last thing I feel is my connections to every one in the hotel and every one I had ever known snap and fall loose like taught thread that’s been cut. The past week in Berlin fell loose in the water too, rippling and sinking, slowly dissolving. That city of gaping wounds, with its ugly gate topped with the awful black chariot and iron cross, passes into the distance and leaves my thoughts. The realization comes creeping that I had never felt more alone. I let the water push me up towards the surface and I float with my face down, my eyes still closed on blackness. I felt my nervous system, wires in unknowable paths and entanglements, drop through my skin, and land at the bottom of the pool, the fragile network of tubes making a gentle thud, while my skin unravels and floats away from me across the water, like a tattered shirt unbuttoned and tossed on the surface. This is where I have ended up and will always end up is my first thought after nothingness. No matter what one does or believes everyone will eventually end up here, at the Van der Valk A4 Schiphol, a helpless victim of entropy, inevitably awry, sent languid to this limbo. Even if I do leave and return home tomorrow, my itinerary will break down sometime later, and I will again be shipped out, unable to penetrate the minds and language of others and understand why. I was subsumed into the whirr of the ticket computer kiosk, the words Schiphol and Unterkunfte, the toucan’s dead eye, the raw rust of the air traffic control center, the endless grass field and rubble road. The hotel in its imperceptible and unstoppable forces had gradually driven me to numbness, slowly pushing me under the suffocating flat sheet of isolation. I, finally and justly, am erased.

I accepted it, until my lungs began to burn. I move my arms slowly as if I just now remember that I have them. I push myself towards the surface, and open my eyes as my head breaks through and into the air. I stand up, my feet find the floor, and chest-deep in the pool, look up at the curved cave of glass that encloses me. The sun no longer beats down and I see white clouds covering the sky. Suddenly, against this firmament and through the glass, a teeming flock of blue-black birds fly in a silent fury, a rush of darting unison. Without chirping or fluttering, their dozens of tiny beaks jut forward, their sharp wings firm at their sides, like jagged marks from a fountain pen across the sky, they streamed past without one deviating from the rest, as if the fleet was a single organism. Taking in the auspices, I stir and stare. The sparrows are arranged like notes carefully written by a scribe into a hymnal to be fervently sung after an ancient priest’s prayer, assembled like flowing data in a chart collected with unclear origin and indeterminate conclusion. The display of concerted movement and effortless coordination was over in an instant, the birds flying past the window lattice. I fell forward, and kicked myself across the side of the pool. I follow them, feeling my body stretch long and push hard, I heave and drag my arms through the water, and swim lap after lap across the pool, kicking and spraying water, gasping loudly for breath with every stroke. I swim until my arms ache, the pain a tonic beat.

Clutching the concrete rim, I pull myself out of the pool. The cool air breezes past my almost naked body, and I let the water drip down my back and fall down my legs. I revel in the sublime sting of chlorine in my eyes. At that moment, I decide I will strut in my too-small swimsuit with bare feet and a bare chest draped in an unused towel into the hotel restaurant, and yell, scream, demand my free meal in my American voice. I will deny my erasure for all the diners to see and hear, drip water, leave wet footprints, and finally make my own indelible mark on the hotel, refusing to allow it to force my silent complacence, my complicity in its nefarious systems, and fly in the face of resignation and helplessness. Maybe other diners will join, yell, demand from our captors a flight home now to Tamilnadu to Mozambique to Sarasota to Saskatoon, or we will unite and rise up and take control of the hotel for ourselves, never leave, and live out our days alone together in this lair with its own food, paintings, and highway exit, away from trouble, danger, the loved ones we inevitably resent. No, no, I decide. I would, must remain civil, it wouldn’t be right, and although I had craved it more than anything, looking out at the immeasurable, singular lawn of the land, I could not bear to feel all their eyes on me as I rail and remonstrate, and fling myself against the hotel, the entropy, the inconvenience, the collective and bequeathed loneliness, against this hotel that I now realize is not a glimpse into the maw of death, but instead the drawing back of the curtain on the scenery of life. No longer jumping at its shadows, I towel off and walk back to my room, leaving no wet trace.

I shower. I methodically put on my clothes and brush my teeth. I walk into the restaurant, humbly present my meal voucher and am given a table. A waiter gives me a plate of glazed chicken and a side of small potatoes. This waiter was the first employee of the restaurant I had really looked at, paid attention to. He is tall and handsome, he moved confidently in his white uniform, and looked exactly my age. He smiled and told me to enjoy. After he leaves, I take in my surroundings and realize I am inside a panoramic bouquet. The room is wrapped in one massive still-life of flowers. It is as if I had landed on the very stamen of a Ruysch painting. On the walls, the petals are voluptuous, curving satin shapes of impossible size, softly holding the tables and diners in an embrace of pinks and purples, violets, lilies, carnations, tulips. All these flowers are at the height of health, perfectly preserved in their sway. I notice no withering and see no bees within their many folds. In Berlin, my girlfriend and I had gone to an art museum, looking through galleries of paintings where Christ was hidden behind meat stalls, in the throng of a dancing wedding crowd, or in the canvas’s corner with mother and donkey leaving bustling fairgrounds for Egypt. I had compulsively taken photographs of every painting I saw. With every click of the aperture I became more and more worried, desperate that I would forget the paintings soon after viewing, that my eyes were not enough, that my memories and the fleeting sensation of first encounter were not to be trusted. She told me that an exhibit in the same museum that I never got to see had focused solely on bees in Dutch still-life painting, and that a friend had written an entire dissertation on these paintings and their iconography. Sitting inside a refracted chamber of these images, each wall lacking a bee, I could not recall her conclusions. Caught in time, the bees may have been a vanitas symbol or one of memento mori; the bee as a vector of pollination and the life-giving harvest, or the harbinger of fecund putrescence, a symptom of that abundance’s rot.

Finishing my meal, I glance across the table and catch color in the corner of my eye. There at the table next to me, also enjoying her meal, is the missionary woman I had overheard on the bus, still wearing her tie-dye dress and wooden crucifix. Looking over across the small gap in space, I imagine her name, where she was born. A small English town, Lancaster, 1955, her name is Flossie. She had a humble upbringing in a large family, her father was a fisherman. She had lost a sister to polio, and found the Church as a way to make a living and understand her feelings of loss. I imagine childhood memories of ice skating on a lake in a blank biting winter, dancing to the Beatles on a fuzzy TV her father saved for, falling in love with her brother’s school friend, but never marrying, finding constancy in her Church, in Christ. She was a flawed singer with an imperfect voice, but excelled in Bible study and even learned Greek to get closer to the text, but she still sings proudly to this day. But how could she believe? Has she ever had any doubt? She must have. What converted her, was it the cry of a child? The meaning in the patter of children playing hopscotch? A dream, a death vision, the searing truth of John 1:1? The explicatory footnotes of her marked-up and dog-eared Bible? The rambling catalogue of Deuteronomy or an ancient manuscript’s liber generationis? Or was it the shining and sprawling marginalia? The miracle of the machine that brought us here, our comfortable, commodious, and economic sky flight complete with infotainment system? Maybe it was one priest’s oratorical power, the culture of her upbringing, a sense of community. How long had she sought proof and does she still? What was the closest to it she had ever been, ever felt? Was it enough to keep going, to fly all the way to Germany to speak to strangers? Was her belief pathological? It couldn’t be illness, I thought, if it was liberating. Still, I knew she woke up every morning with the cross heavy, sharp, and tight at her chest, to another day of searching, and maybe finding, what? A solace, a meaningfulness. What would she say if I reached over and touched her shoulder, for I am that close, and asked her how and why we ended up here?

That night, in just a few hours, we would sleep in the same building, she and I, and then awake. Walking the same path through the delft jar corridors, boarding a plane, and flying across the blue sky and white clouds behind windows, we complete our crossing. We found each other here, maybe we will again. I want to catch her eye and smile at her softly. I look over at the woman in the tie-dye dress, and think it like seeing the world’s colors and shapes shimmering through the diaphanous film of a wasp’s wing.

Owen Monroe is a senior in Columbia College and will receive his degree in May, 2020. He is double majoring in art history and English. Owen is originally from Providence, Rhode Island, but is currently taking the coronavirus quarantine one day at a time with his parents in Southwest Colorado. He would like to thank his friends and family for all of their support and guidance during his four years of college. Check out another nonfiction piece of Owen’s published in the University of College London’s Student Magazine (pages 30-32) here. Instagram | Facebook