1. girl holding on to summer by a thread

This girl wears a skirt that hits her ankles, brushes against the tender space between her protruding bone and Achilles when she walks, moves around her as she goes, a thin, black fabric painted with rich blue flowers. She imagines the flowers are freshly plucked: that their petals turn wet when fingers are pressed into their skin, its life fading out of itself and imbuing the skirt in unfurnished edges—a fleeting of moment of life caught between the fabric of this skirt. She hopes she can carry the life the skirt possesses; she hopes it may save her right now.

She wears this skirt walking across the parking lot of a mini-mart to her car holding one large bag of Cool Ranch Doritos, the hem occasionally brushing against the asphalt, while she charges ahead through the sprinkling rain as if her head is pulled by a string. She opens the door of her car, a hunk of metal seventeen years old and no longer quite alive with its windows that don’t roll down and its air conditioning that doesn’t work. It belonged to her father and was given to her when she got her license less than a year ago, an overeager sixteen year old looking for any kind of independence. The car is silver, almost mirrored looking as it reflects the rain—Ag, she knows, is the symbol for silver on the periodic table. When she learned the periodic elements she remembered this, Ag is silver, something precious among symbols of unknown liquids and gases, intangible things. She remembers reading in an encyclopedia once about the antiquated belief that silver possessed divine properties and people believed that silver warded off vampires and beasts. The grace of god lived in silver, pierced the souls of beings that lived less.

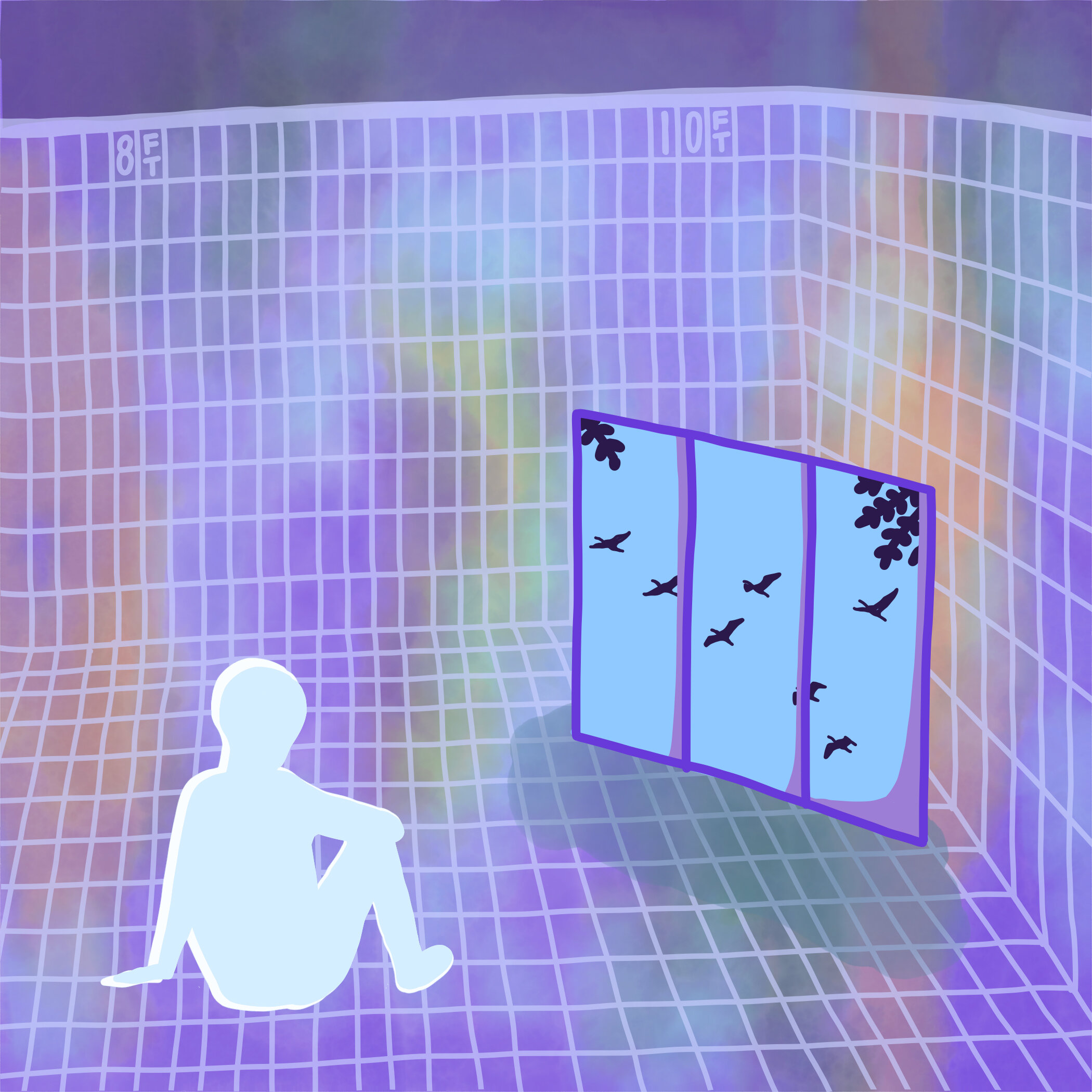

She sits down on the grey leather seats and closes the door so that the world outside becomes muted, viewed through her windows like a television screen. She hopes that silver has the supernatural properties madmen once believed it to, that this vessel can protect her from the world that lies beyond even if to believe so makes her mad as well. She has already seen enough of that world to know what there is to fear, what there is to lose, and will take the moments of safety she can.

The band of her skirt pinches at her waist where a small roll of newly accumulated fat tips over. She is not as svelte as she was just months ago, but likes to think of herself as now possessing more heft, a stronger gait, before she would ever let herself believe she has grown chubby. She leans her head back against the headrest but cannot bring herself to start the engine, and closes her eyes instead. When she opens them she thinks she may have fallen asleep, and is not sure how much time has passed. She checks the clock on her dashboard, which reads 12:07. She had closed her eyes for three minutes at most, but sees already that the rain has moved from

somewhere between a mist and a sprinkle to a drizzle as drops condense and slip down her windows, the sun shining through them from between the clouds.

It is November. The weather in this time and in this particular part of California is meek and not yet decisive enough to be winter or even fall, it is characterized the most by its inability to fit one or the other. No clothes suit this weather, no styles, no bodies. Instead she finds herself a little too cold most of the time, a bristle of her skin and goose bumps the norm as she continues to dress down instead of bundled, just as she had in the four or five months before this change of weather. A moment passes and she runs the engine, and begins driving through the silence.

Eventually she reaches the boatyard, where the people wait for her with his ashes. She is cold. The skirt she wears trails in her wake, its fine material probably not fashioned well for the weather or the place or the occasion, and grows damp and stained shades darker by the rain. The gathering is small, the dock shared between five people wearing shades of black so close to grey they vaguely resemble the clouds above. Three of them aren’t important to her, nor were they to her father, and the only other there is the mother she won’t look at. This mother does not look at her either, stares at the ground somewhere past the dock through to the water, which pricks against light rain. The girl knows that if they look at one another they will only see how alone in the world they both are now. There is no acknowledgement needed for her to know that she and her mother both feel the burden shared between them, and the question of whether or not they can carry it feels impossible to answer now.

They spread his ashes in the ocean. She doesn’t look at the water as they fall because she read once that when ashes are thrown in the ocean, fish come to the surface and eat them. She cannot lean over to look, cannot grant her self the knowledge that this is in fact what happens to him, but also can never object to them being thrown here because that is what he wanted. The rain still does not come down hard enough to really be called rain, but it is just hard enough that her hair both frizzes up and limply clumps together, just hard enough that she cannot tell what her face is wet from, cannot tell whether she is crying or if it is only this weather.

After the ceremony she leaves the boatyard with everyone else but sits behind in her car, watching them all drive away. When they leave she grabs the Doritos she purchased at the mini mart that day, smashes the bag against her body and allows it to crinkle, breaks apart the chips inside as she walks back towards the dock. She stands in the spot they stood to spread his ashes and pulls at the back fold of the bag to open. Delicately, she throws the crumbs across the water as they had done before, and hopes for two things: that she is not too late, and that fish like Cool Ranch.

2. girl swallowed whole, in a steamed pork bun

When she was still young enough to divide her life in inches grown, her mother dragged her feet between the pantry and the fridge and straight to the trash bins outside her home, hauling red cans of Chef Boyardee, bright yellow cardboard boxes of Eggos and blue ones of Rice Krispies, taking Snap, Crackle, and Pop with her. Garbage, she called it, trans fats, she yelled out. The girl cried the next day when a Chef Boyardee commercial came on while watching TV with her brother and sister, a can of Chef Boyardee autonomously rolling down streets and hills straight into the home of a family infinitely whiter and cleaner and stronger looking than hers—concerned that it was one of the cans her mother had thrown in the trash.

"Home" had always been a hard place to pinpoint. She had wanted, at one point, for those gracious boxes of preprocessed foods to be home, looked for it watching TV with her sister, tried to see it reading book-upon-book aloud under the covers of her bed in the smallest room of their large suburban home. She did not see it at school, could not find it in the soles of her shoes, or lingering along her tonsils when she looked in the mirror and stared down her throat. She did not hear it in her own voice, or her parent’s Cantonese or Shanghai dialects that she couldn’t understand well enough to laugh in.

When she is fifteen her cousin passes away, the one who she once thought was her older brother and who had been her sister’s best friend, and she learns that she had in fact, always known how to eat her way home. Her cousin was several years older than her and a soldier, always serious, had just turned twenty-three when he had stopped on the side of the highway to help someone stuck with a flat tire and a semi-truck took the space of his life and drove away.

She did not eat Kellogg cereals or Chef Boyardee after he died, but she did stow away in the back of her closet for eight hours and ate her way through four bags of chips and a pack of Oreos that tasted slightly salty with her tears, which endlessly seemed to drip into her food for all the table manners that she never developed. She swallowed without tasting or chewing much, looking to fill herself in some way, and then even full, still she shoved bite after bite in her mouth. She didn’t slow down until the day after his funeral when her family went to dim sum, because one can only eat so hastily using chopsticks.

At their usual restaurant they are seated by their usual waiter. She takes her seat at the back of the table as they all wait for any word from her aunt, his mother, a woman with ash in her hair and smoke for breath, a woman who, in this moment, possesses the skin of a soup dumpling.

The girl is not hungry. She doesn’t know if she can eat right now, doesn’t know if she will ever eat. Instead she thinks of starving until her body begins to eat itself, feasting away at her own muscles and bones and whatever is left of her, until it disappears altogether. She stares at her food, the dishes the same as they always order but for the first time in a room plagued by ghosts, everything silent while the food sits untouched, like an offering to be made to spirits not yet allowed to be dead.

She passes time naming each plate. She has never been fluent in Chinese, but has always known enough to speak the language of dim sum. When she was small at family birthdays her grandmother spoke to her in her best English, which was always spattered with phrases of Cantonese. Her grandmother would point to the dishes and made totem poles out of them, all stacked upon one another in towers of bamboo steamers, each with a different meaning: the little peach-shaped steamed buns were for immortality, a whole fish was for wealth, orange slices for dessert were good luck. Long noodles were for a long life.

She can only think now about whether or not her cousin had eaten enough long noodles,. She tries to remember if he did, recalls the weekend mornings they would so often spend right here, all the memories blurring into variations of themselves. She can see her seven cousins sitting in every combination, her grandma swatting at their skinny, tan little arms as they reach over the lazy susan. She can see them all lean over her sister’s lap to peer at a game of Pokémon under the table, and pour tea from as high as their tiptoes allowed them. She remembers how it "felt to call this place, these foods, home. There was always a certain comfort in knowing the

secret code to flip the cap of the teapot for a refill, the right way to hold chopsticks. It is correlation or causation, she isn’t sure which, but to be whole was to have these meals that always left her chest and stomach stretching for capacity.

She remembers what is no longer, her whole family together, the home she realizes has always been right here. She stares at the array of foods that once brought a warmth that overwhelmed her, a warmth like the steam that rises from a fresh bamboo platter of soup dumplings, like the golden glow of an egg tart, like unfolding the lotus leaf wrappings of sticky rice. That warmth like childhood, like nostalgia, like home—a warmth that appeared in front of her, that had once stared right back at her, but today is not here.

There is so much to grieve. A can of Chef Boyardee, the comfort of a cup of chrysanthemum tea, a cousin. Someone grasps her hand under the table, and she looks to see that it is her mother, carrying tender expression and chopsticks already poised over her plate. “Here,” she whispers, breaking the silence, taking a portion of whole fish from a large China platter. She puts it on her plate for her without asking further. “Eat it for good luck. Head to tail. Beginnings to endings.”

Her aunt smiles at this in the slightest of ways, her cheek muscles pulling upwards, her skin wrinkling in tiny indentations. Her sister begins to fight her cousin for the har gao, her youngest cousin pours them all tea. She sees still that thing that has given all, that has destroyed and created and made generations persevere. She sees hope: The feelings of home, family, and warmth can still exist, will always exist as long as the memories do. For this moment she allows herself to eat, as every bite reminds her of who she has been, of where she comes from and what this food means. It is the best way that she can begin to let herself remember. She breathes. She

still knows how it feels to find herself in the pockets of a steamed-pork-bun, and for all broken Cantonese she remembers too as her grandmother had told her, that dim sum means a little bit of heart.

3. girl without words

She did not mean for it to happen. No one means for it to happen.

Did she say no?

She is not sure anymore. She had told him she was too tight, she told him she didn’t want him, that he would hurt her.

But whether or not she had said “no”—that one word with whatever protections it could or could not have provided—she does not know anymore and does not want to bring herself to remember, even as it has just happened. She does not want to think there is anything “no” could have done for her. It should not make a difference. Either way, it is too late.

She told him she didn’t want to go further, and he said he liked it this way as he locked the door, pushed her on to the bathroom floor holding her hands down against the cheap linoleum tile. It was a party in the house of a girl she was sure didn’t know her name, From somewhere beyond she could hear the sounds of Top 40 music and voices layered on top of voices in conversation, could hear people she had hoped to dance with dance, could feel their rhythms and noise vibrate through her body. She listened closely, tried to pick out the individuals songs and their lyrics. Justin Bieber’s “Love Yourself” was playing. She hated that song, because she was never sure if he really wanted this girl to love herself or hate herself, was never sure if perhaps he believed that there were just some people not deserving of even self-love. She remembered the quote she had loved last year as a senior in high school, one she found on the internet by Mehreen Kasana, a writer she had never heard of but admired ardently: “A woman of color’s self-love is political and radical, and it is unsettling for the status quo because she is

choosing bravely to dismantle the narratives of racist aesthetics against her.”

She had only every wanted to find home in herself, in her tan skin and girl’s hips and the sway of her breasts that were, since fifteen years old, her favorite part of herself. But writhing under his body, she understood that she could never be granted such a privilege. She was not strong enough to make her body home, was even so weak she had allowed her body to be destroyed in minutes. She thought she already learned to know all that grief could be, and perhaps she did, but it did not compare to the sharp sting she felt in her own body as that boy

stretched her in all the wrong ways. She listened instead to the voices outside of people she might know, focused on their sound over the grip of his meaty hands and the weight of his thick body and his hot, wet breath lingering on her neck.

When he finishes, he peels his body off of her and kneels over her, grabs her hand as he gets up, pulling her to stand on knees inverting upon themselves. He tosses her the clothes she had been wearing before all of this, and when he notices her shaking, asks what’s wrong with her and then leaves before she can answer.

She decides she will make it home herself, cleans blood and semen from her body with toilet paper because she does not want to stain the hand towels in this unfamiliar house, and calls an Uber home. The friends she came with see her walking outs and ask her why she leaves. They do not prod her when she manages only to say that she did not want it, they let her go even as she hopes they realize what she is trying to say. Part of her thinks they do, but do not want to deal with her realities.

She wakes up in her own home the next day, and smells her mother cooking breakfast and her sister watching Saturday morning cartoons, and can hear her father making his coffee.

There is some chafing and a bruise on the small of her back now from when he had pushed her down, from the way her skin had rubbed against the floor as he moved. Everything between her thighs burns whenever she so much moves, and she finds herself unable to speak, unsure how and with whom to share her burdens. She cannot tell her parents—she doesn’t know how would they think of her if they knew she was not so pure, was starved and dry and dirtied inside by a boy who was not supposed to touch her. She steps out of her bedroom and walks past her family in the kitchen and the living room unseen, walks out the front door and into their driveway. Her father’s pickup truck is parked on the curb, and pajama-clad and barefooted, she hoists herself into its bed and sobs.

A week ago, she would think this something George Saunders could twist into perfect fiction, that she would rather hear the romantic simplicities of this experience than its truth. She thinks of reading Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street, the first book she found herself between the words of, and the vignette Sandra writes like this, a vignette she had thought was beautiful but is unsure now how Sandra could ever say what happened to her even in the vaguest terms. She thinks of all the fictions she has read of this violation, all the ways they could never

compare to her now. She thinks of everything that has happened to her in just this last night, that she could not have imagined yesterday morning.

It is then that one of her friends who had been there the night before calls. She gets enough words out of her to understand what has passed, and is on her way immediately. Her friend arrives before the sun has yet budged in the sky, and she is still sitting in the bed of the truck. Her friend brings a hand over her mouth and points to her pajamas and she realizes then that she is bleeding, has bled through her clothes and onto the truck’s plastic lining, a small puddle of dark, discharged blood mixed with dirt and dust, and these are just the elements of life.

In the end her friend convinces her to call their old teacher, the one who taught them sex-ed last year in grade eleven. The girl asks her friend to speak for her, the girl says that everything important is stuck to the linings of her insides, too thick to leave her body, but asks her friend not to say the word that begins with R. The girl has always thought that words were capable of carrying the weight that humans are unable to bare, but right now she cannot think of the implication of what that word can carry, not now after she knows what it means.

“A boy did something to her,” her friend tells their teacher, tongue tripping over the “something.” “That she didn’t want to him to do. And now she’s bleeding all over, and please, please tell us what to do. I don’t know how to help her. We just don’t know what to do.” She and her friend have both managed to let tears fall down their faces, and she can hear now that her friend speaks in between gasps. She burns, and she does not know why her friend is allowed to be breathless when this has happened to her, when for her friend these words still lack their meaning.

She can hear their teacher speaking slowly from the other line. “First, tell her I’m so sorry that happened to her. If she’s there she should know that this is not her fault. This does not change who she is. Secondly, tell her to go to the ER or Planned Parenthood, and consider calling a crisis hotline.”

Their teacher gives them directions on how to see Planned Parenthood, on how she would report the incident. She tells them they can ask her for anything, to call her back every hour just to check in with her they can. When they hang up on her, her friend drives her to Planned Parenthood. It sits in a complex that also contains a Taco Bell, perched on the side of a road that lives somewhere between street and highway and has not been repaved in a long time. The sun is already low and there is no AC in the Planned Parenthood, where they spend three hours in the waiting room sweltering under blinding fluorescent lights and walls the shade of newborn-baby-girl pink.

A nurse eventually takes her in, a young woman in pastel purple scrubs that against the walls starkly remind her of her childhood pediatrician’s office. When the nurse asks her what happened she just says that a boy was too rough with her, cannot elaborate on her lies. The nurse examines her, tells her that she is torn inside and bleeding. She tell her that it will take at least a month for her to heal naturally, that for that month she cannot use tampons or have sex or do any rigorous physical activity and should take Advil each day, that she could spot at any given moment and that there is nothing she else she can do about these things.

The nurse asks her if it was consensual, and then asks her again, and then a third time. Each time she cannot respond but nods, and then starts to cry. The nurse holds her by her arms and rubs them gently, tells her that if this was consensual that she cannot let someone do this to her, cannot let anyone wreck her inside, cannot let someone hurt her like this. And then the nurse turns around and tells her she is free to go, moves on to the next walk-in.

She walks back into the dreamy-bright waiting room where her friend sits, reading People magazine. The moment her friend sees her she stands wordlessly and they leave the complex, walking past the Taco Bell and into their car. When she finally speaks, she tells her friend that she wants to report this boy, wants to make sure he know what he did and can never do this to anyone else again. Her friend suggests she call the crisis hotline first, and she grabs her phone and begins to dial.

A deep voiced woman picks up, her tone disinterested. Her friend tells phone woman the short of what happened, still avoiding the R-word. The phone woman falters, tells her she is sorry that happened to her, her voice sounding too much like grief and now-sunken desires to help others. Her friend asks what would happen if she reported the incident and the phone woman goes over the procedure, asks if she’s had a kit done, if she’s been to the ER, tells her the police would investigate and only if there was sufficient evidence a district attorney might pursue the case.

“And what happens then?” her friend says. “Will he go to jail?”

“I’m so sorry,” Phone woman says, and the girl can hear her heartache, a miniscule reflection of her own. “I don’t know what will happen. In the end, it could be nothing. It could just be your word against his.”

ab extra: girl never empty-handed

Your first boyfriend liked to draw you in charcoals—dark shadows and soft edges. You let him. You were only fifteen then, and you thought that perhaps if you could immortalize his love for you it would make it true, that it would make it stay.

You were silly, too young for your love to be real but all too ready to participate in the aesthetics of it. All thick hair and doll eyes, a petite nose and delicate skin that possessed a translucent veil of youth and a warm glow off its surface, you were born ready to be a muse, to let men look at you, and, so young, he was ready to partake. You held small hands firmly sweating, pressed patchy dry pink lips to cheeks, and sat on floor with legs crisscross saying that love could look like this, love was meant for you.

You later found love did not come packaged in Wes Anderson movies set and timed and screened to be perfectly looked at. Real love was messy, and you had enough mess. You wanted beauty. Selfish and greedy after being hurt for so long, you wanted the trim edges and flourished words, and only those. You broke up with your first boyfriend, and then you simply found another to hold on to, and later another, and then another, all loves that looked the part.

You came to them all with ribbons in your hair, embroidered with dogs and pink flowers, mixed tapes labeled with lyric quotes in cursive, sweaters three decades old taken from your mother’s closet. You let boys look at you with your locks loose over your shoulders, swathed in your relics, and they believed then that you only let them see you like this, that this was your bare self and not curated from the history of you, not a regal presentation. And you knew from the way they looked at you that you would always have this.

You had few people who you allowed to see you un-fashioned. One was a girl dark-haired and tanner, who smiled at everything you said and never wavered in the face of your faults or your false liabilities. When a boy does to your friend what young girls are taught to fear, fed statistics of “1 in 5 girls” before they have the agency to choose their own clothes, aesthetic love and beauty are not weapons that can be used, cannot be crutches the way you have always willed them to. So you reach for your friend’s hand and buy her a bag of Epsom salts, drive her to Planned Parenthood, and call for help. You realize then that she has crept up on you, that you care about her more than your boys and facades of love, that you love her bleeding and torn and that she would love you the same.

As a child, your favorite book had been The Velveteen Rabbit, the story of the beautiful little toy’s search for realness in his world unscathed. The final answer is delivered by the Skin Horse, his words long silenced in your memory, but never lost to you: “Real isn't how you are made, it's a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real ... Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don't matter at all, because once you are Real you can't be ugly, except to people who don't understand.”

You do not know when you let things become real.

You bring her gifts each day without pretension, after the salts the next day you bring chocolate because there is no heartache chocolate cannot soothe, and the next day you bring beets. You read once that red velvet cake was first made with beets during the Great Depression, a trifle of a delicacy in a world unbreathable, shrouded in dust. You decide that your friend must survive now too.

And so you take flour and sugar and roast beets, peel and cut them until they dye your skin a thin red that is near pink, a translucent glow that settles between the indentations of your fingerprints. You beat in eggs and drive cream cheese to mix with powdered sugar, bake something not quite red and heftier on one side. Your frosting is chalky with sugar and weighs down the sides, uneven and lacking sheen. You use Betty Crocker Decorating Gel in 1980s-bright, neon purple and pink, and write the best thing you can think to say. It is no paragon as it should be, no perfect imperfection, but it is also uncalculated and real, and today, it is the only thing that you have.

When you gift it to your friend, she smiles and cries and laughs and says it is all she could want right now, eats three slices and does not care that it is sickeningly sweet and a smidge dry, and nothing has felt better in all of your life. The cake reads, I LOVE YOU ALWAYS, MY BEST HUMAN.