We made that same trip every summer for as long as I could remember, landing in Tehran in the delicate hour just before sunrise, after nearly a whole day of traveling. Back then, a handful of European airlines still dared to fly to Iran from the United States through Amsterdam or Frankfurt. Once, on a long layover, I fell asleep in a tourist-packed square in Amsterdam and woke up with a backache from the granite bench, blinded by the sun, panicked and then furious at my mother, who had shaken me awake. I remember the German airline always had the best toys. They came in velvety cobalt pouches that I loved to rub in between my fingers. Inside there were playing cards and a miniature airplane, and a gold plastic pilot’s badge you could pin to your shirt. My cousin Ali and I would play cards for hours, side by side in the dim light of the cabin until our mothers hissed at us to sleep.

Upon every arrival déjà vu would cloud my senses, made hazier and more surreal by my half-asleep state, making it seem like we had made this journey a thousand times in the same way. Like my whole life had been spent in those unfriendly halls. Officers lined the walls, young, with curly black beards disguising their youth. They were always checking our bags, running them through the scanners over and over, opening them and rummaging through the American riches we had brought for our family—bulk vitamins from Costco, Nike tennis shoes, baby clothes from Gymboree. I would eye the guns in their holsters and be overcome with paralyzing fear, convinced that I had committed a terrible crime without knowing it. I imagined my parents being taken away for questioning, locked in a windowless room, beaten and kicked. It never happened—not to us, anyways.

We’d emerge from passport control in a bleary haze aboard huge escalators, descending at a glacial pace to the arrivals floor. Year after year I would grip the handrail for balance and my mother would slap my hand and tell me it was dirty. So I would sway in place, looking at the just-mopped, gleaming tiles below us, the baggage carousels beginning to stir awake. On the far side of the lobby stood a glass partition behind which families were gathered in clumps, peering up at us, the weak blush of sunrise fighting through the choked-up atmosphere just visible through the windows behind them.

As we made our descent, I would compulsively search the crowd on the other side of the partition, my heart thumping in my chest, until my gaze struck upon the familiar features of a cousin or an aunt, immediately sending a shock through me. I would retreat, jerking my head away and pretending I had not seen them—though I was certain I could feel the hot weight of their gazes on me—until we had collected our bags and wheeled them to the other side of the glass to properly greet them.

Once we passed through the doorway and I heard their voices rise up to greet us, I could no longer keep my eyes fixed on the floor. I had to actually look up at them, into their eyes, my aunts with deep laugh lines and jolly cheeks and their gruff husbands and their children, the cousins I could have grown up with but instead regarded with unease.

There were rounds and rounds of hugging and kissing. Generally, the unspoken standard procedure is two or three air-kisses on the cheek, one on each side of the face, where you don’t even have to make contact so much as just bump cheekbones with the other person. But when you are a child being greeted after a long separation, the rules of ordinary cheek-kissing, and more generally physical boundaries, tend to go out the window. Everyone’s lipstick ends up smeared on your face. The aunts, numerous as they were, especially could not get enough of me. I marveled at their formidable energy, their inexhaustible ability to embrace me ten or twenty times, pinching my cheeks hard, with gusto, running their hands over the thickness of my hair, demanding to braid it. They rattled off an unending fountain of questions while we all did our best to haul the luggage outside. Fifty different ways of asking after our health. I tried to answer. Nothing I said seemed adequate. Responding with something like ‘good’ or ‘fine’ in response to a how-are-you-adjacent question didn’t seem to do anything to stem the flow of these questions. They would simply inquire again and again, more earnestly, eyes wide, as if the asking was supposed to accomplish some other goal and my answers were entirely extraneous to the process.

At this point I would become consumed by uncertainty. It was not so much a matter of linguistic incompetence (I was, after all, the best student in the Saturday Farsi school in our corner of suburban America) so much as what I came to view later in life as a pathology peculiar to my shy, anxious nature. When had everyone learned the words to the script, and why didn’t I know it? I could not think of much to say at all, could only fall back on threadbare phrases: salaam, chetori, khoobam. On the car ride from the airport to the hosting relative’s house, I would lean my head on the window and pretend to fall asleep, relieved that I finally had permission to lapse into silence.

As I grew older my communicative incompetence began to weigh on me more, as I could rely less and less on my youth to excuse my peculiar behavior. I was sure that my aunts were clucking in pity behind my back, that my cousins only spoke to me out of obligation. This only led me to be quieter. But one particular summer, I was still young enough that my self-consciousness was only budding. I was much more preoccupied by an impending change in wardrobe: this year, I was old enough that I would have to start wearing a headscarf out in public.

At nine years old the connection between the clothes that my female relatives in Iran wore outside of the house—long, loose pants, a manteau to the knees, a roosari covering their hair—and my father’s ramblings about the Islamic Republic was shadowy at best. I knew certain facts: that my cousins in Iran hated their Qur’an class in school, that my Aunt Marzieh and her husband had been political prisoners and were now exiled (was that the Shah’s fault or the regime’s? I was never quite sure) and that was why Aunt Marzieh’s children could never visit their vatan but could only get as far as the Persian grocery named Vatan in a local (American) strip mall instead. A year before, in the summer of 2009, the Green Movement had ripped through Iran and sent shocks through our small diaspora too. My father had taken me to the arthouse cinema downtown to see a documentary about it, and there, sitting in a plush red velvet chair, I watched the little boy onscreen cross the street to buy some yogurt and get shot in the head. My father covered my eyes too late.

And yet—this summer, as my mother tied a scarf around my head for the very first time, I felt an unexpected, undeniable thrill. To get to dress as a grown-up woman, to be visibly marked by femininity, was exciting. Although, as I fidgeted with the tight knot she had tied underneath my chin, I still felt uneasy. It had something to do with the suspicion that my father would no longer take me as seriously. Perhaps I already knew that I would lose the ability to come and go between their two worlds the way I could go between the men smoking outside and the women washing the dishes after dinner.

I wore my green paisley roosari proudly for the first few days of the summer, constantly pushing it forward so that no hair was visible, but it soon lost its charm and became a suffocating nuisance. Tehran was famously hot and dry, sitting in a kind of bowl-like topography that trapped pollution and kept it sitting low, crammed on top of the city. Each time I ventured outdoors I returned feeling dizzy and thoroughly desiccated, immediately downing most of the potable water in the household, which spurred another excursion to buy more bottled water from the corner shop. The aunts, who went out only wrapped in even more fabric than I did, clucked in pity. She’s an American child; she can’t withstand this heat. They eventually forbade me from going outdoors. I was embarrassed and miserable, not only because I was causing problems, but also because I had to stay home all day with Fafa.

Aunt Farideh (everyone called her Fafa) was my mother’s oldest sister and the worst aunt of all. She had never married and lived in identical dingy apartments throughout her life, financed by the men in her family, first her father and then her brothers. Fafa was old and perpetually ailing and mostly refused to leave her home. She presided over the parlor in a large leather reclining chair like a tiny, shriveled queen and rasped orders at one of her two nursing aides while vwatching Turkish soap operas from morning until night. Twice a day, her aide lifted her out of her armchair and delivered her birdlike body to an upright wooden dining chair, in which she would smack and chew a few bites of rice, and then return her to her throne in front of the television.

I knew that I was supposed to love Fafa because I was related to her. When we gathered cross-legged on the floor to eat dinner that night, I stared at her skeletal body folded into her chair and her sour, leathery face, and I tried hard to love her.

Fafa chewed her rice and watched the television, oblivious to the intent behind my gaze. I watched the motion of her jaw as if in a trance. Her gnashing seemed to grow louder and louder the more I paid attention to it, until I had to put my spoon down and cover my ears. Of course I couldn’t get away with that for long. Someone murmured something to my mother, who in turn elbowed me roughly.

Resigned, I dropped my hands and picked my spoon up again. I couldn’t love Fafa. I couldn’t muster up any affection towards her at all. I felt badly for the rest of the meal, but only in a vague sort of way. I was mostly ashamed that my mother had an emotionally defective child who was not devoted to Fafa as she was and I was scared that someone would find out.

For the next few days, I avoided everyone by curling into whatever corner of the apartment I could hide in and plowing my way through my library copy of Gone With the Wind, which I was reading with great attention because my mother had told me I was too young for it. I was careful to have my hand covering the title when she was around. But she found the novel one day anyways while going through my suitcase, gave me a sound scolding, placed it on the highest shelf of a cupboard, and locked it.

The next day my mother and one of my cousins decided to walk to the convenience store on the corner together. I argued my way into accompanying them. For a few moments it was pleasant—I breathed in the familiar scents of gasoline and cigarette smoke as we walked along the side of the road, practiced reading street signs, tried in vain to pet the stray cats that meowed for food at screen doors before my mother dragged me away, shrieking about filth and diseases. At a busy intersection I hesitated while my cousin dashed ahead of us and crossed the street, in front of a huddle of bored-looking soldiers with their hands resting on their holsters, following her movements with their eyes.

By the time we made it to the shop, I was red-faced and complaining of lightheadedness, and more of my hair had escaped my headscarf than was hidden underneath it. My mother, exasperated, bought me a juice-box of peach nectar, roughly re-tied my roosari snugly around my head, and instructed me to go to the restroom in the neighboring office building and splash some water on my face while she finished the shopping.

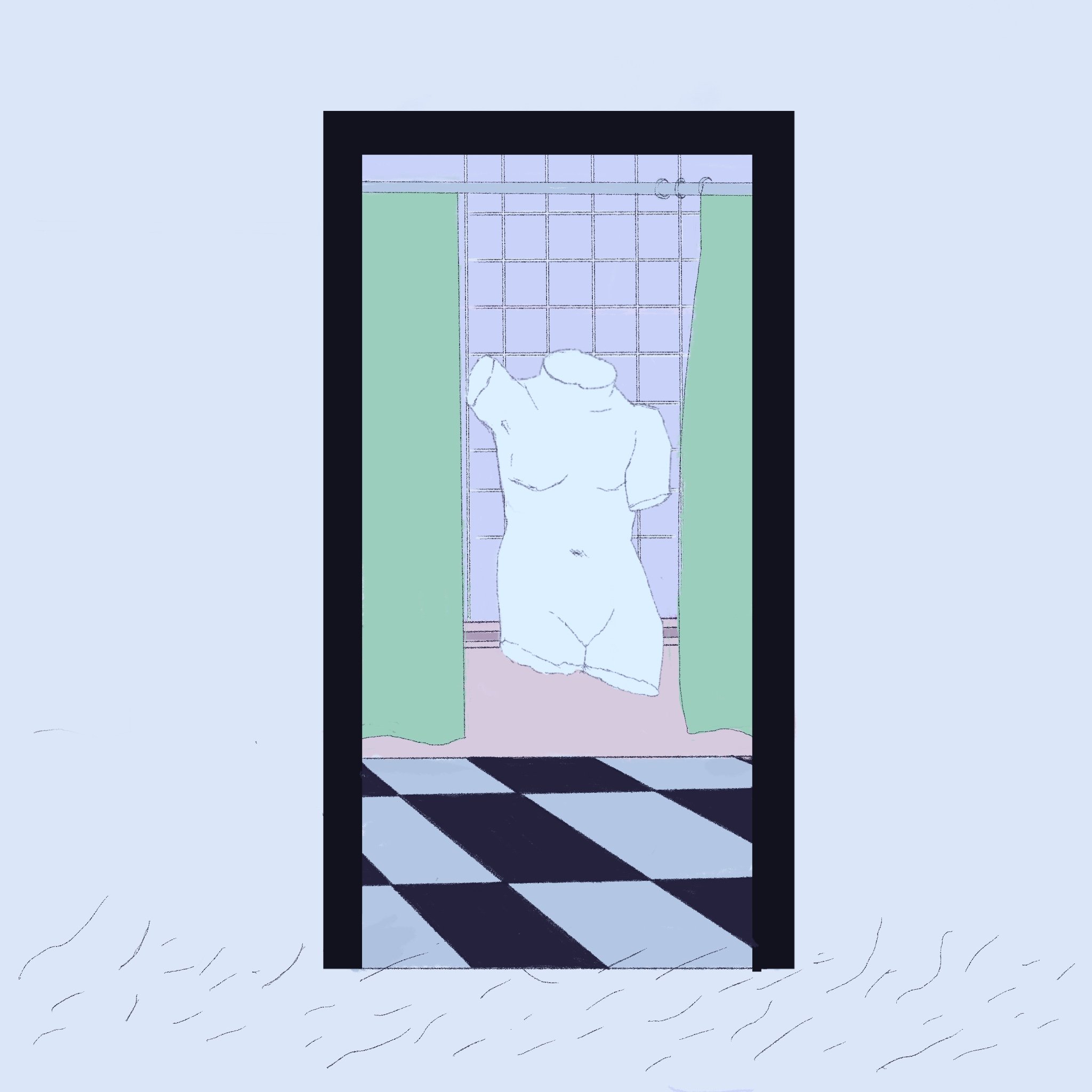

Inside it was cool and deserted. My shoes squeaked on the tiles. I stumbled into the bathroom, head woozy from the heat, my heart beating hard in my throat. For a moment it was completely dark inside and I fumbled blindly along the wall for what seemed like long minutes, searching for a light switch, until they automatically blinked on. I peeked inside one of the stalls, hoping that there was a ‘foreign’ toilet (i.e. a Western-style toilet and not a hole in the ground) that I could sit on—there was. I carefully balanced my juice-box on the edge of the sink, then entered the stall and locked the door behind me. I sat down on the toilet lid with a huff, looked down, and was surprised to find that my legs were stained with fat drops of scarlet. As I stared, they seemed to multiply.

A few seconds later, my senses caught up and I felt it, that sinister metallic trickle from my nasal passage down to the back of my throat where it didn’t belong, and then I realized that the heat radiating from my face had manifested in a fat gush of blood pouring its way down my body from my nostrils. It flooded down my chin and over my closed lips, worming its way all over my teeth and into my mouth when I opened it in surprise, then onto my legs, staining my T-shirt with the monkey on it, dripping on the tiles beneath my feet.

I imagined leaving the bathroom covered in blood, how my cousin would wrinkle her nose in pity, letting everyone know that I had made a mess. Panic rose in my throat. I tried to breathe through my clenched teeth, to tip my head back and raise my left hand—was it the left or the right?—as I had once been taught to staunch the flow, but all at once the blood redirected down my throat and I choked, and anyways it was too much, too fast, it was everywhere. Still trying to keep my head tipped upwards, I felt blindly for the toilet paper roll next to me and tore off a measly thin square—the last piece.

Blood was dripping faster from my chin. By instinct, I opened my mouth again and sound burst forth—not speech but a ragged sob, in the primal language of infancy, something I thought I had outgrown. I gasped for air and tried to conjure up words, but for a few terrible moments, there were none. Like dipping a sieve into water searching for the tiniest bits of silt—I could not retrieve any bits of language. The pathetic piece of toilet paper was already soaked through, and red was running further down my wrists. Then all at once, miraculously, a bit of speech turned up and wound its way out of me—and I screamed, triumphantly, Maman!

I was marched home with a wad of rough paper towels up my nose, drawing looks (or so I imagined) from passersby on the street. And I was relegated once again to sitting at home with Fafa. I spent a long time in the shower, crying inconsolably, no doubt driving up my uncles’ water bill by dumping bucket after bucket of water on myself.

An hour later I finally emerged from the bathroom, teary-eyed, the ends of my hair dripping onto the carpet beneath my bare feet. I found the living room empty besides Fafa in her usual position, nestled in her reclining chair in front of the television. I paused in the doorway for a moment. We both watched the screen attentively, listening to the melodious stream of rounded, fronted vowels emerging from the lovely lipsticked mouths of the actresses.

Suddenly Fafa turned her gaze on me. I stared back. Her eyes, usually cloudy, were lucid and sharp and shone out from her dried-apricot face, searching mine.

I decided to retreat, and tentatively stepped backwards, back into the hallway.

“Come here, dear,” she snapped. She thrust out a spotted, gristly limb from the nest of blankets covering her body and outstretched a hand, so gnarled by age that it seemed more like a claw. I swallowed, dutifully approached the tiny queen, and laid my hand gingerly in hers.

“Setareh joon, Setareh joon,” she murmured to herself, stroking my hand. “What a pretty young lady you’ve become.”

For the rest of my life this habit of calling little girls ladies would irk me. It didn’t make sense, first of all, to call a child a lady from the moment she is born. What was the purpose of blurring that distinction right away? And it was obvious to me that I was still unmolded, roughly shaped, nowhere near what one could call a lady. In fact, I would probably never become a lady because, as everyone could see, I was born in the wrong place and was growing up wrong and would no doubt stay this way. I could barely keep a headscarf on my head for twenty minutes. The air in Tehran made me sick. The graceful linguistic rites of the women in my family, one thousand elaborate and eloquent ways to say thank you demurely and heap goodwill on your host and guests alike, were an indecipherable mystery to me.

I shivered and stood mutely, frightened of her gaze, looking away towards the television instead. The queen onscreen was engaged in tense conversation with her lady-in-waiting, and her lovely spill of dark hair kept falling in front of her shoulders and obscuring her face. I bowed my head a little so that my hair would do the same. “Thank you,” I finally said quietly. Silence fell. There was something more to say, something better, but what was it? I didn’t know.

It was at this moment that Fafa decided to inflict upon me something uniquely terrible, another unhappy experience of childhood: Out came her other hand from underneath the blankets, index and middle finger outstretched and curved into two fleshy sickles, and she firmly grasped a bundle of flesh on my cheek in between her fingers. She squeezed, hard.

She was still cooing some nothing-words at me that I couldn’t quite make out. My eyes were watering. I tried to politely twist out of her grip, but her fingers were stiff and strong—she had hooked me like a fish. I stood there, helpless, bent oddly over her chair as she pinched and twisted my cheek, feeling my heartbeat once again thudding in my ears and that odd tightness caving my chest inwards, too bashful to rip myself out of her grasp with any real force.

A few agonizing minutes—or maybe only seconds, I don’t know—passed, until something red dripped onto Fafa’s quilt, leaving a lurid stain against the faded floral pattern covering her lap. At first she didn’t notice. More drops fell, with an urgency in their splatter. An ugly metallic taste pricked the back of my throat. Fafa’s grasp on me slackened, finally, and she shoved me away from her with a shout of alarm. I leaped backwards, victoriously, hand to my stinging cheek, and allowed myself a small grin, made gruesome by the blood streaming down my chin, and dashed away into the safety of the bedroom without a word. I locked the door behind me.

Tara Shabazaz (she/they) graduated in 2024 from Barnard College studying Linguistics.